☆☆☆☆☆

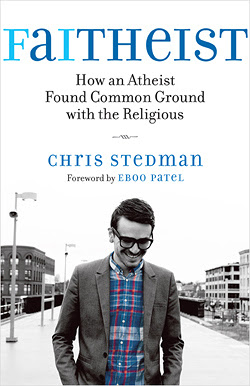

The Humanist Book Club adopted Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious for its December discussion in preparation for an author visit to Bryant University, co-sponsored by the Humanists of Rhode Island. I found the book alternately challenging and exasperating, but its limitations are mitigated by the youth and inexperience of the author and chronological development of the memoir. Most often, the questions he raises in one part of the book, he resolves elsewhere. The logical inconsistencies are suggestive of a young author who has yet to resolve every nuance of the issues that preoccupy him. Who has?

Faitheist is a memoir. While the standards of scholarship do not apply, Stedman lays out on page 11 what is arguably his thesis. He defends atheist participation in Interfaith activism in terms of maximizing resources for promoting social and economic justice. Elsewhere in the book he acknowledges that Interfaith nomenclature is alienating, but insists that participation is worth it. To my mind, whether or not it is worth it is a matter of perspective and life trajectory. The year Stedman had already invested in divinity studies when he renounced his faith and his established support network would seem to favor his decision to remain.

I sympathize with Stedman's plea for less stridency. There is a point at which ridicule can be construed as coercion. But a call for restraint from an Interfaith activist is bound to be taken as putting Interfaith activism ahead of the atheist cause. The question of loyalty must certainly account for a fair share of Faitheist bashing.

|

|

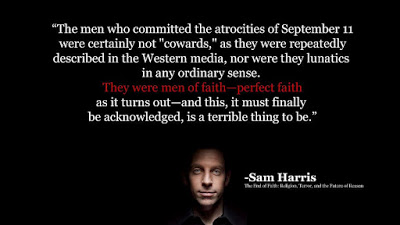

On page 12, Stedman continues the thread of atheist antipathy toward religion. He attributes the desire to eradicate religion to a pessimistic vision. Those of us who see the vision of a world without religion as an optimistic one will be inclined to disagree. Perhaps nothing more is the operative phrase here. Seeing religion as nothing more than a problem to be eradicated suggests reducing people to mere obstacles rather than seeing them in their full humanity. Then again, we're talking about eradicating religion, not religious people. Can we hate the delusion but love the deluded as the religious hate the sin but love the sinner?

Stedman addresses any doubts about where his loyalties lie on pages 149-150. He renounces false equivalencies between the intolerance demonstrated by atheists toward believers and that of believers toward atheists. He also acknowledges the diversity of atheist opinion. Understanding that diversity of opinion should prepare him to defend atheism in his Interfaith work.

|

|

Religious extremists and moderates lay rival claims to authenticity within their faith communities. It is reasonable, however, to ask whether more harm is ultimately done by enabling religion or prevented by humanizing it. Faitheist is a good place to start if you're interested in challenging your own position. It is a respectable first book by an author who has discovered an original niche for himself. His will no doubt be an indispensable voice on the subject.

Knowledge can easily represent a robust application regarding cutting down poverty and joblessness and accomplishing a maintained human being improvement. If we compared our country schooling with some other developed/developing country, grab my essay for all kind of papers writing and it is very essay from others any writing service providers.

ReplyDelete