☆☆☆☆☆

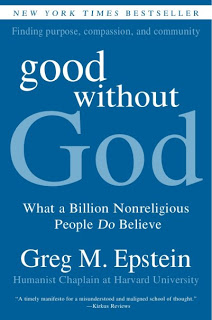

Good Without God , by Greg M. Epstein (2007), was the Humanist Book Club selection for our inaugural meeting in July. There could hardly be a more appropriate choice for a first meeting than this primer on Humanism. Epstein's book gives Humanism a concise but comprehensive treatment, but is given to moments of intellectual vacuity. Epstein's simplifications might be forgiven in light of his conscious effort to write in a way that is accessible to the uninitiated.

Epstein describes Humanism in the Introduction. So far so good.

Humanism rejects dependence on faith, the supernatural, divine texts, resurrection, reincarnation, or anything else for which we have no evidence. To put it another way, Humanists believe in life before death.

More formally, the American Humanist Association defines Humanism as a progressive lifestance that, without supernaturalism, affirms our ability and responsibility to lead ethical lives of personal fulfillment, aspiring to the greater good of humanity.

Also in the Introduction, Epstein entertains the question of whether Humanism is a faith. Unfortunately, he does so in a way that glosses over the differences between optimism of the will and optimism of the intellect. He seems to suggest that faith in humanity is a willful delusion. There is a difference between acting

as if you believe in a favorable outcome and acting

because you believe. If we do nothing, we are assured a negative outcome. Humanity is its own best hope because we're all we have.

Faith in God means believing absolutely in something with no proof whatsoever. Faith in humanity means believing absolutely in something with a huge amount of proof to the contrary.

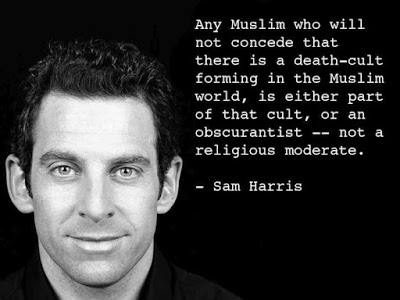

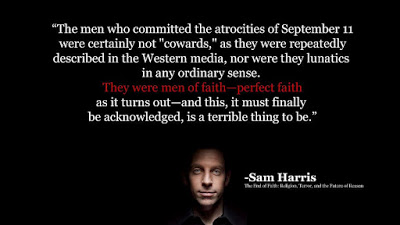

Epstein gives a nod to Dawkins, Harris and Hitchens in the Introduction, only to pick a postmodernist fight with an science, reason and the New Atheism. This is a tiresome straw-man argument. There is no danger of being too rational or scientific. Rationality is as organic to humanity as emotion, instinct, and intuition. Anyone governed by pure rationality is a psychopath. Saying "don't be a psychopath" is a superfluous warning. As for science, it is just a more rigorous variant of the informal hypothesis-testing we do unconsciously as we experience and learn about the world.

But atheism goes astray when it adopts a certain posture, one best captured by a cover story in Wired magazine in November 2006: "The New Atheism: No Heaven. No Hell. Just Science."

The mention of three of the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse is curious for its omission of Dennett, who directly confronts the problem of postmodernist relativism.

In the first chapter, Epstein returns to the question of Humanism as faith. His discussion could have benefited from finessing the difference between faith in a truth claim and faith in a principle. Moreover, his wordplay is suggestive of the obscurantism that he later repudiates. He executes a successful course correction by declaring his commitment to reason.

Call Humanism a faith if you like--we should have no particular allergy to that word--but recognize that it is a faith in our ability to live well based on conclusions and convictions reached by empirical testing and free, unfettered rational inquiry. In other words, we question everything, including our own questions, and we search for as many ways as we can to confirm or deny our intuitions. We have no holy books meant to be taken at face value or blindly obeyed. We are open to revising any conclusion we have made if new evidence appears to contradict it. (p. 10)

Epstein denounces mockery of religion. Whenever accommodationists call for civility, I have to wonder whether they understand the difference between deriding irrational beliefs and debasing irrational people. Do they understand that the only reason blasphemy is shocking is that religion has enjoyed a protected status and that shielding untenable beliefs from criticism is the reason such ideas persist? Does he understand that the collateral damage of hurt feelings is the price we pay as a society for freedom of expression and that freedom of expression is the only way to insure that the best ideas prevail?

The point is not to mock religion, but simply to drive home that we have high standards when it comes to deciding whether a story is true or not. (p. 11)

He begins to redeem himself when he aptly points out the irrelevance of the question. "Do you believe in God?" With the concept of God defined so broadly, the more pertinent question is "What do you believe

about God?" Epstein answers on behalf of Humanism.

Here is the Humanist answer: we (the nonreligious, atheists, Humanists, etc.) believe that God is the most important literary character human beings have ever created. (p. 13)

Epstein turns to modern religious reformers who have infused religion with humanistic principles. He begins with Paul Tillich, who redefined faith as "the state of being ultimately concerned." Here, Epstein reclaims the Humanist repudiation of obscurantism.

Tillich's is a popular, influential, and widely respected approach to theology, yet he makes the difference between an atheist and a Christian into nothing more than a slippery semantic game. (p. 15)

Also noteworthy is Epstein's treatment of John Dewey.

Essentially Dewey proposed a formal, lightly refined version of Spinoza's theology. God was not in the universe, but the positive forces in the universe as far as humans were concerned. Dewey was not exactly a pantheist, but rather called himself a "Reconstructionist"--one who reconstructs the definition of the word God in order to refer to natural human values instead of a supernatural deity. (p. 17)

Mordechai Kaplan, who founded Reconstructionist Judaism was influenced by Dewey. Epstein also observes that Oprah's God of personal empowerment is indistinguishable from a Reconstructionist god. Of of this is to say that Humanism's only quarrel with obscurantists is their obscurantism.

If you believe in Spinoza's god, Dewey's god, Tillich's god, or Oprah's god, we Humanists are your allies and friends. But we believe that calling what you believe in "God" is at best utterly irrelevant to whether you're a good person, and at worst it can confuse and distract others and even you from what is really important. (p. 17)

As Epstein dedicates his book to Sherwin Wine, it would seem an omission not to mention him in a review. Epstein mentions six form of atheism that vary along the dimension of theistic probability but result in

de facto atheism, living

as if there is no god.

There are different kinds of atheism. The first is "ontological" atheism, a firm denial that there is any creator or manager of the universe. There is "ethical" atheism, a firm conviction that, even if there is a creator/manager of the world, he does not run things in accordance with the human moral agenda, rewarding the good and punishing the wicked. There is "existential" atheism, a nervy assertion that even if there is a God, he has no authority to be the boss of my life. There is "agnostic" atheism, a cautious denial that claims that God's existence can be neither proved nor disproved; this type of atheist ends up with behavior no different from that of the ontological atheist. There is "ignostic" atheism, another cautious denial, which claims that the word "God" is so confusing that it is meaningless; this belief, again, translates into the same behavior as the ontological atheist. There is "pragmatic" atheism, which regards God as irrelevant to ethical and successful living, and which views all discussions about God as a waste of time. (p. 18)

From the God question, Epstein transitions to the implications on a Humanist lifestance. He begins with the evolution of cooperation.

From a detached, coldly scientific standpoint, measuring only whose genes get passed on, the lives of our siblings, not to mention our children, mean almost as much to us as our own lives. But it would be a sad world if the passing on of family genes was only reason to be good to one another. (p. 22)

There is something vaguely postmodernist about Epstein's association of science with cold detachment. At this juncture, Epstein turns to walking the reader through the evolution of cooperation via direct reciprocity (tit for tat), indirect reciprocity (paying it forward) and the evolutionary advantage of group selection.

As Darwin said in The Descent of Man, there is no doubt that "a tribe including many members who...were always ready to give aid to each other and sacrifice themselves for the common good would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection. (p. 24)

Epstein anticipates the usual objection to social Darwinism--asserting that Humanism disavows it--and transitions to hypotheses about how religion became ubiquitous if not adaptive in its own right. He explains that religion may have been a byproduct of some other adaptive features.

When you take a good scientific look at the human mind, God is not a gene, but a spandrel. A spandrel is the triangular negative space created between two archways when they are positioned side by side, often elegantly decorated in churches and other imposing architectural structures. Evolutionary scientists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin first pointed out that this term, and the idea of a spandrel in general, can explain something critical about our God-beliefs: that they are by-products, not adaptations. (p. 26)

Although these hypotheses fall within the scope of evolutionary psychology and present methodological challenges to empirical testing, they are valuable in that they offer a counter argument against the

assumption that religion is adaptive and therefore good. Epstein explains that causal reasoning is responsible for our tendency to assign purpose to unexplained events. Theory of mind, in turn, accounts for our ability to ascribe motives to real or imagined actors. It is also our source of empathy. Taken together, causal reasoning and theory of mind form a

spandrel of faith.

Well, belief in God is also a by-product of two of the most important architectural features of our minds: archways of our brains that produce the spandrel of faith--what cognitive scientists call "causal reasoning" and "theory of mind." (p. 26)

Having explained the ubiquity of religion without affirming its utility, Epstein employs Plato's dialogue

Euthyphro (380 BCE) to drive home the point that goodness is independent of any gods.

In the dialogue, Socrates reminds his friend Euthyphro that a crucial question is not simply whether we can know if one or another particular action is good, but on what basis we determine whether any action is good. Euthyphro answers: "Piety, then, is that which is dear to the gods, and impiety is that which is not dear to them.

But Socrates responds: "Is that which the gods love good because they love it or because it is good?" (p. 32)

After a discussion of Thomas Nagel's ethics--that radical selfishness leads to unhappiness--Epstein turns to a morality based on needs and contracts. He then walks the reader through the emergence of humanism from the Lokayata and Carvaca, to the contributions of Jefferson, Darwin, Marx, Nietzche and Freud, before rendering another concise definition of Humanism.

Humanism is an acknowledgement that a meaningful life is a moral life, and a moral life is a meaningful life. (p. 63)

Having dedicated attention to western liberalizing influences, Epstein turns to Buddhism He relates his personal experience as a westerner drawn to the "exotic" religion. He was ultimately deterred by Buddhism's emphasis on detachment.

For Humanists, it is good to desire, and it is good to care. The questions are; what do you desire, and what do you care for? Humanism's message is no more or less than: be passionate about things that are worth being passionate about. (p. 80)

Epstein further describes Humanism in terms of dignity. To this end, he returns to Sherwin Wine.

He defined it by describing its four qualities: "The first is high self awareness, a heightened sense of personal identity and individual reality. The second is the willingness to assume responsibility for one's own life and to avoid surrendering that responsibility to any other person or institution. The third is a refusal to find one's identity in any possession. The fourth is the sense that one's behavior is worthy of imitation by others."

Along with these four characteristics come three moral obligations for the person who values them: First, "I have a moral obligation to strive for greater mastery and control over my own life." Second. "I have a moral obligation to be reliable and trustworthy." And third, "I have a moral obligation to be generous." (p. 90)

In an intimately self-conscious confession, Epstein reveals his trepidation and purpose in writing this book.

Suddenly, once I realized that the purpose of this book was less to advance my own career and more to help others to advance their lives and address their fears, my own fear of failure began to melt away into insignificance. (p. 102)

Having connected his purpose to helping others find dignity, Epstein returns to Sherwin Wine on the subject.

The dignity of mutual concern and connection and of self-fulfillment through service to humanity's highest ideals is more than enough reason to be good without God. (p. 103)

Having declared himself on the side of helping others to live with dignity, Epstein summarizes the argument for tolerance of religion by atheists in terms that evoke a similar mutuality.

If the emotion I cultivate is hate, or indifference, or bitterness, then that's what I will become, and it doesn't matter if my so-called enemies have earned the scorn, because now I have given over to it. (p. 156)

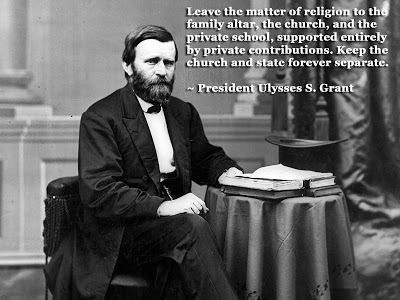

As an antitheist, I am inclined to see religion as deserving of all the scorn that comes its way, but I avoid absolutes such as "you can't go too far." When you become toxic to yourself, you have probably discovered a good place to draw the line. Given the prevalence of religious belief, antitheism could become self-destructive if not tempered with pragmatism. The best guidelines I have discovered for coexistence with the religious comes from Daniel Dennett's view of religion as a "worthy alternative" rather than a "sacred cow."

As might be expected, Epstein's call to tolerate the religious leads into a justification of atheist inclusion in interfaith work accompanied by concrete suggestions. From there, Epstein transitions to Humanism's religious roots.

Regardless, for better or worse or both, modern organized Humanism began, in the minds of its founders, as nothing more or less than a religion without a God. (p. 169)

Epstein attributes the founding of religious humanism to John Dietrich, and its popularization to Curtis Reese and John Potter. He then discusses the importance of religious identity and community, as well as the sense of transcendence that believers experience.

As the neuroscientist Andrew Newberg explains, regular ritual participation creates "resonance patterns" in the brain, making mystical experiences that shut off the "self" more likely, by confusing the parts of the brain that track our physical boundaries and map the space around us. And when it isn't shutting off the self, religious worship can help people focus on difficult problems. In a moment of crisis, the act of kneeling, lowering the head and whispering Dear God, I need you" may seem helpful only insofar as it provides a relationship to the deity or divine intervention. But it actually provides an opportunity to collect oneself and marshal internal resources that might otherwise go unnoticed or untapped. (p. 180)

As a Humanist alternative to prayer, Epstein recommends a technique from Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, developed by Humanist psychologist Albert Ellis. The technique is known as an "ABC" (Adversity-Belief-Consequences). The good that religion does, however, is arguably to alleviate the symptoms of the very ailment it incubates.

The central idea behind [REBT-ABC] is that our emotions and behaviors are profoundly connected to our thoughts, so by changing your thinking, you may be able to positively affect your future thoughts and actions. (p. 181)

Epstein ends with a look forward, offers suggestions for organizing Humanist communities. His comparison of organized secularism to herding cats points to the resistance of Humanists to the mindless elements of organized religion. In presenting the objections as impressionistic, he dismisses them. When Atheism+ supporters characterized Humanism as "churchy," I found the characterization lacking in precision--too impressionistic to be constructive. On the other hand, there may be something behind the impression that trained Humanist leaders are too priestly, especially if they take too much umbrage when the cats don't flock like sheep.

Esptein seems to take it personally that his efforts are politely dismissed instead of accepting the responsibility of selling his vision to a population predisposed to reject it. What is missing is the acknowledgement that the predisposition is born of laudable qualities. It's a self-serving logic that blames an ungrateful constituency. To be fair, building Humanist community is arguably a worthwhile endeavor. I personally enjoy my local Humanist community. The challenge is to make a forceful case for a meaningful personal investment without the expectation of universal appeal.

For too long, organized secularism has been an oxymoron, like herding cats. People who believed in a more humane, Humanistic world mostly wrote off the possibility of gathering their peers together so that together they could actually have some influence. Weekly meetings were too dogmatic. Trained leaders were too priestly. Dedicated meeting spaces were too churchy. (p. 217)

Good Without God is a wealth of information about Humanism and an excellent primer. It is not a primer on atheism, as the reader who has read the Four Horsemen will have an advantage. Epstein is at his best when compiling and synthesizing information objectively. While reading his book, I sometimes found myself shaking my head and thinking that he had missed the point somehow. As an antitheist, I found Epstein's most compelling point to be that disdain for religion can be toxic for the atheist. While insincere reverence for religion is still a form of submission, taking the high road does not necessarily concede the point. A concession to our higher selves is just that. Finding a way to coexist with the religious may be a lifelong struggle, but who wants to live an examined life?